Dispensational Federalists affirm the body of truth commonly referred to as The Covenant of Works.

While many dispensationalists might think an affirmation of The Covenant of Works would concede too much, Dispensational Federalists do not take significant exception to the body of truth that is commonly espoused under that designation.

The typical objection from dispensational quarters is that the Bible never explicitly uses the term ‘covenant’ in relation to Adam. Hosea 6:7 may prove otherwise, but irrespective of that, it hasn’t always been this way. Historically, there have been a number of notable dispensationalists who were quite comfortable understanding the relationship between God and Adam in covenantal terms.

S. Lewis Johnson gives evidence of this by saying, “In the Scofield Bible we have reference to what happened in the garden of Eden as being of a covenantal nature, and that’s true, in some of the editions of the Scofield Bible you will find it referred to, Genesis chapter two and Adam’s probation, as the Edenic Covenant.” [1]

Now, what could be more dispensational than the Scofield Bible?

But to reinforce this, Charles Ryrie says, “The ideas and concepts contained in the Covenant of Works and the Covenant of Grace are not unscriptural.” [2]

And if your patience allows a third witness, contemporary dispensationalist Michael Vlach also acknowledges, “The covenants of Covenant Theology are not what’s most important. Traditionally, three covenants have been affirmed in Covenant Theology”, And then he adds, “some Dispensationalists have affirmed one or all three of these covenants while remaining dispensationalists.” [3]

And that is the point we are trying to make.

But what exactly is affirmed when people talk of The Covenant of Works?

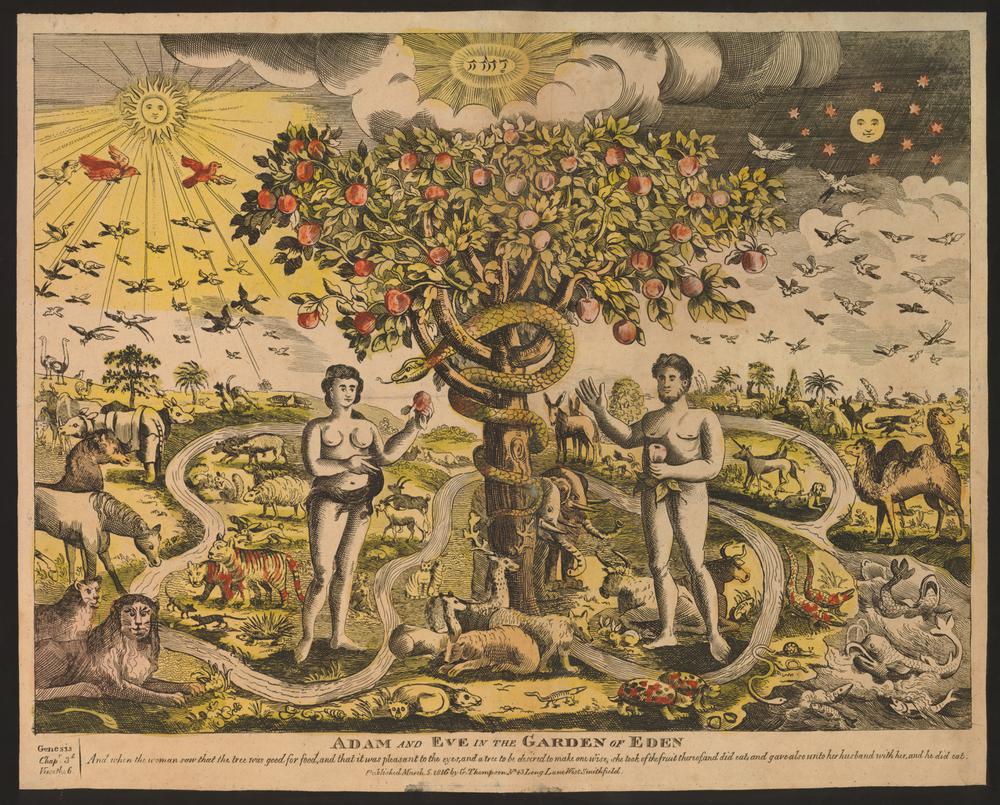

Typically, it refers to the terms of the relationship between God and Adam in the garden of Eden. It is thought of as a probation period, where Adam was threatened with the punishment of death for disobedience (Genesis 2:17) but was also implicitly promised life for obedience, where he would have been confirmed in a state of righteousness. But the critical aspect of this relationship is that it was governed by the principle of Representative Headship. Adam’s obedience or disobedience would result in the corresponding blessings or curses, and these in turn would be counted to those he represented, to all of mankind.

But its the tight parallels between the first and second Adam that are so important for us to understand. Any exegete worth their salt, whether dispensational or otherwise, should affirm the biblical principle of Representative Headship (Romans 5:12-19, 1 Corinthians 15:21-22). That should be the bare minimum. But as soon as that is acknowledged, the extent of the parallels between the two federal heads need further consideration. The implications are important.

J. V. Fesko highlights this by writing, “Two alien principles, righteousness and sin, come to people from without.” [4]

This means that the imputed alien righteousness of Christ, which I hope all affirm, finds a corresponding alien imputation in the doctrine of Original Sin. Adam’s sin came to mankind by immediate imputation. It came to us via the terms of the relationship that God had put in place in the garden. Then, when our union with Christ is explicitly described as The New ‘Covenant’, it shouldn’t really surprise us if some think of the corresponding union with Adam in the same covenantal terms.

What is clearly taught in the bible is that the terms of the relationship with Adam were representative in nature, they were conditional, they were based on Adam’s works, and they held forth both promises and threats for obedience and disobedience. But call it what you like, I think its fair to admit that the ingredients are all there and something closely akin to a covenant should be affirmed.

While discussing The Covenant of Works, S. Lewis Johnson also said, “One must learn right at the beginning that covenant theology is not different from dispensational theology in everything that covenant theology teaches, there are points that overlap.” [5]

For Dispensational Federalists, this is another point of overlap and our conclusion is this; The Covenant of Works does not undermine any distinctively Dispensational beliefs. This is an area of agreement, and our differences lie elsewhere.

Many covenant theologians affirm three overarching covenants. The Covenant of Redemption, The Covenant of Works, and the Covenant of Grace. And so far, as we begin to sketch an outline of a Dispensational Federalism, we haven’t taken particular exception to the first two. From here it should be evident that our differences must stem from our various understandings of The Covenant of Grace.

In the articles that follow, we will begin to look more closely at our differences. Because we do still have significant differences!

[1] SLJ Institute, The Divine Purpose, The Fall of Man and the Messianic Promise, or The Covenant of Grace

[2] Charles Ryrie, Dispensationalism, p189

[3] Michael J. Vlach, Dispensationalism Essential Beliefs and Common Myths

[4] J. V. Fesko, Death in Adam, Life in Christ, p53

[5] SLJ Institute, The Divine Purpose, The Fall of Man and the Messianic Promise, or The Covenant of Grace