Many theologians use the substance/administration distinction to navigate the complexities of the mosaic covenant. In defending the validity of this approach Geerhardus Vos claimed, “Paul nowhere sets the Sinaitic covenant in its entirety over against the Abrahamic covenant”.[1]

But when John Owen came to study Hebrews 8:6, this is exactly what he saw. The Bible frequently presents the Mosaic covenant in contrast with the Abrahamic and New covenants.

To Owen, the thesis that the mosaic covenant was substantially gracious couldn’t bear the weight of the biblical data. Jesus was not the mediator of a better administration; he was the mediator of a better covenant.

He translates Hebrews 8:6 in this way,

But now he hath obtained a more excellent ministry, by how much also he is the mediator of a better covenant, which was established on better promises.

Approach No. 3 – John Owen’s Covenant Theology

In his famous commentary on the book of Hebrews, Owen explains that the author here, ‘takes occasion to declare the nature of the two covenants’ and that, ‘this other promised covenant should be of another nature than the former’.[2] He concludes that the two covenants in view are the Mosaic and New Covenants. He is not suggesting the typical twofold administration of the same covenant of grace. He is stating that the two covenants differ at the level of substance.

Owen asks a key question in these words, ‘Here then ariseth a difference of no small importance, namely, whether these are indeed two distinct covenants, as to the essence and substance of them, or only different ways of the dispensation and administration of the same covenant.’[3] And to answer he says, ‘scripture doth plainly and expressly make mention of two testaments, or covenants, and distinguish between them in such a way, as what is spoken can hardly be accommodated unto a twofold administration of the same covenant.’[4]

After stating that these two covenants are not only compared to each other, but are also diametrically opposed to each other, he then gives his biblical basis for his position. And he does so just as dispensationalists typically do, by citing 2 Corinthians 3:6-9, Galatians 4:24-26, Hebrews 7:22, and Hebrews 9:15-20.[5]

To Owen, the Mosaic Covenant was, ‘no other but the covenant of works revived.’[6] He saw in the Mosaic covenant, ‘the nature of that first covenant’,[7] meaning the covenant of works made with Adam before the fall, where all the, ‘inexorableness as unto perfect obedience, was represented.’[8] He believed that the Mosaic Covenant, ‘revived the sanction of the first covenant, in the curse or sentence of death’[9] and also that it even, ‘revived the promise of that covenant, that of eternal life upon perfect obedience.’[10]

But we still want to see Owen get beyond the confusion and answer the critical question, how can the Mosaic Covenant be considered a Covenant of Grace and a Covenant of Works at the same time? How does understanding the Mosaic covenant as a covenant of works allow for salvation by grace, through faith, for those living under it?

Owen continues, ‘We must grant two distinct covenants, rather than a twofold administration of the same covenant’ and then he adds an important caveat, ‘We must, I say, do so, provided always that the way of reconciliation and salvation was the same under both.’[11] And this brings us to his answer.

After stating that the Mosaic covenant doesn’t share substantial unity with the covenant of grace, and anticipating the typical Reformed objections, he obliterates them by saying, ‘But it will be said, and with great pretence of reason, for it is that which is the sole foundation they all build upon who allow only a twofold administration of the same covenant, “That… if the way of reconciliation and salvation be the same under both, then indeed are they for substance of them but one.” And I grant that this would inevitably follow, if it were so equally by virtue of them both. If reconciliation and salvation by Christ were to be obtained not only under the old covenant, but by virtue thereof, then it must be the same for substance with the new. But this is not so; for no reconciliation with God nor salvation could be obtained by virtue of the old covenant.’

By ‘old covenant’ he is referring specifically to the mosaic covenant. And with this brief stroke of his pen, he has just satisfied the demands of his most significant objection.

Owen is saying is that salvation always continues to be by grace to those living under the Mosaic economy, ‘that the way of reconciliation with God, of justification and salvation, was always one and the same’,[12] but soteric grace is not located in or via the Mosaic covenant itself.

He then proceeds to show precisely how the Old Testament saint was saved. And in answering this we see the real genius of his argument. It boils down to the fact that, ‘whilst they were under that covenant… all believers were reconciled, justified, and saved, by virtue of the promise’.[13] He believed that the Abrahamic covenant, ‘was no way abrogated by the giving of the law, Gal. iii. 17.’[14] This is to say that the Abrahamic covenant remained operative throughout the mosaic economy. And by considering the Mosaic covenant as ‘organically independent’, it retains its truly conditional nature, while at the same time, the Abrahamic covenant of promise can be seen as a pure expression of grace. Both aspects of Law and Gospel run parallel, perfectly simultaneous, yet unmixed and uncompromised in their integrity.

This approach allows for the continuity of salvation by grace to those living under the Mosaic Covenant and a sharp discontinuity with the conditional nature of the Mosaic Covenant that is presented in the Bible. This is the only covenantal structure that maintains the razor-sharp clarity of the Law/Gospel distinction. And this is what I believe is the best form of Reformed covenant theology.

But what may come as a surprise to some, is that this view of the mosaic covenant is what dispensationalists espouse!

When dispensationalists historically affirmed the conditional nature of the mosaic covenant, they were incessantly charged with believing in two ways of salvation, or of having no grace in the age of law. In response Charles Feinberg said, “dispensationalists have repeatedly pointed out the falsity of the charge… do they intend to teach that there was no grace in the age of law? No, they mean no such thing. Ever since Adam sinned, it has been God’s grace that has saved man”.[15]

Just like Owen, the better dispensationalists believed that “The Law itself did not disannul the promise”.[16] They believed that the mosaic covenant was added (Gal. 3:19) and that the Abrahamic covenant remained operative throughout the mosaic dispensation. Salvation was always by virtue of the promise which would ultimately find its fulfilment and substance in Christ.

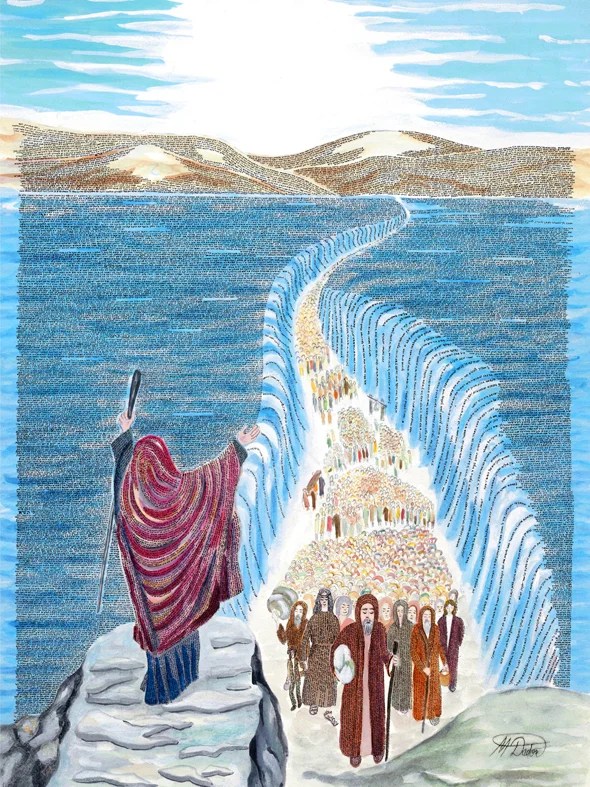

Perhaps the best illustration of this is found in Exodus 32. Israel had just broken the Mosaic Covenant by worshipping the golden calf and Moses returns up Mount Sinai to plead forgiveness for the sins of the people. Based on the Law alone, their utter destruction would be justified. But in this exchange with God, we see where grace is located during the mosaic period. Here, it is evident that Moses doesn’t plead forgiveness based on the law, for there is none, but his appeal is based on the promise to the fathers. In other words, he pleads the Abrahamic Covenant.

Conclusions

First, with this understanding of the mosaic covenant, one can successfully affirm the conditional nature of the mosaic covenant while simultaneously maintaining the unity of salvation by grace throughout redemptive history.

Second, Dispensational Federalism didn’t begin with Darby. It has its roots in the Reformation.

Third, every self-respecting dispensationalist should consider themselves a covenant theologian.

[1] Nicholas T. Batzig, Geerhardus Vos on the Mosaic Covenant and the Covenant of Grace, Vos, Reformed Dogmatics, p76-80

[2] John Owen, Exposition of Hebrews, Volume 6, p49

[3] John Owen, Exposition of Hebrews, Volume 6, p69

[4] John Owen, Exposition of Hebrews, Volume 6, p76

[5] John Owen, Exposition of Hebrews, Volume 6, p76

[6] John Owen, Exposition of Hebrews, Volume 6, p78

[7] John Owen, Exposition of Hebrews, Volume 6, p77

[8] John Owen, Exposition of Hebrews, Volume 6, p77

[9] John Owen, Exposition of Hebrews, Volume 6, p77

[10] John Owen, Exposition of Hebrews, Volume 6, p78

[11] John Owen, Exposition of Hebrews, Volume 6, p76

[12] John Owen, Exposition of Hebrews, Volume 6, p71

[13] John Owen, Exposition of Hebrews, Volume 6, p77. I have reversed the position of these comments for clarity. Owen’s point remains unchanged.

[14] John Owen, Exposition of Hebrews, Volume 6, p64

[15] Charles L. Feinberg, Millennialism, p225

[16] Charles L. Feinberg, Millennialism, p219